It’s landed, a really thought-provoking report by the film-maker, Christopher Hird, on how journalists can achieve impact with their work, funded by the not-for-profit foundation, Adessium. I edited the report, which is over 100 pages long, and you can read it here.

I also blogged about it for the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which commissioned the report, and my blog is below. I’m reposting it as I think the report raises important points for those interested or involved in public interest journalism.

In Investigative Journalism Works: the Mechanism of Impact, a report for the Bureau, journalist and film-maker Christopher Hird quotes the reporter, Horace Greeley, who said: “The moment a newspaperman tires of his campaign is the moment the public notices it.” The aim of this report, commissioned by the Bureau and funded by the public benefit foundation, Adessium, was to look at how journalism can have an impact in the world and get the public to take notice. This is particularly important for not-for-profit media organisations like ourselves; our mission statement states that our core work is in “exposing the facts, informing the public, holding power to account”.

One of the key messages from Hird’s report, which I edited for the Bureau, was that journalists, if they do have an intended aim with their journalism, need to be patient. It requires long-term commitment from editors too, something demonstrated, in particular, by Harold (later Sir) Evans, with his campaign to secure justice for families affected by Thalidomide, discussed by Hird in Chapter Two of our report.

Some journalists debate whether not we should campaign and have clear aims for the end of every journalism project. Others are more comfortable with campaigning – there’s a spectrum of opinion stretching from what one might term pure reporting (exemplified by channels such as BBC Parliament and newer organisations like WikiTribune) through to campaign-led journalism by specialist outfits such as Global Witness and Greenpeace. One of the key messages of Hird’s report is that campaign-led journalism doesn’t have to be a poorer (and, to some, slightly disreputable) cousin to investigative journalism. If anything, Hird argues, with more not-for-profit journalism funded by philanthropic organisations, the return that they seek, in Hird’s words, is “transformation, rather than transactional”. To that end, one key recommendation of the report is that media organisations (following on from some in TV) consider appointing impact editors/producers, who work alongside journalists to achieve desired change.

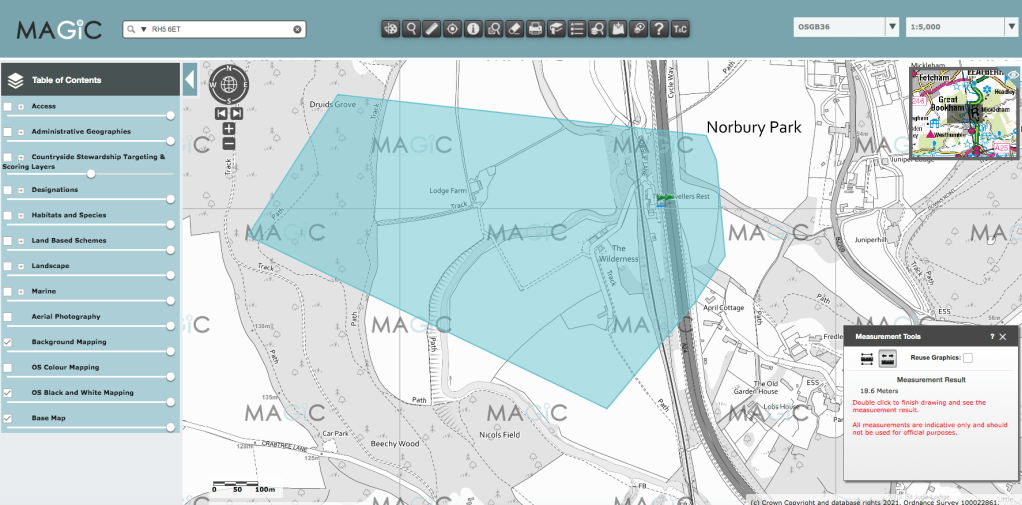

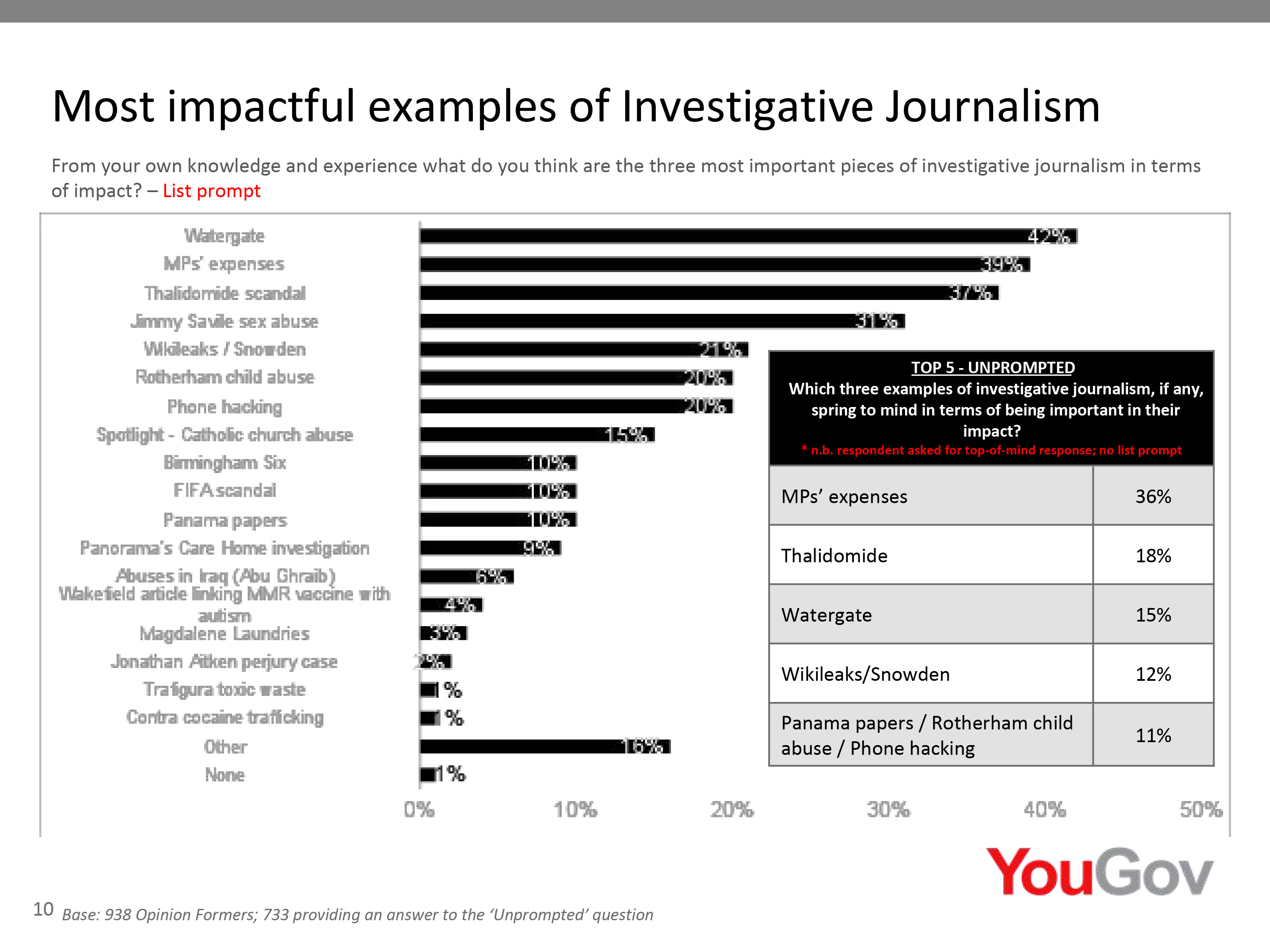

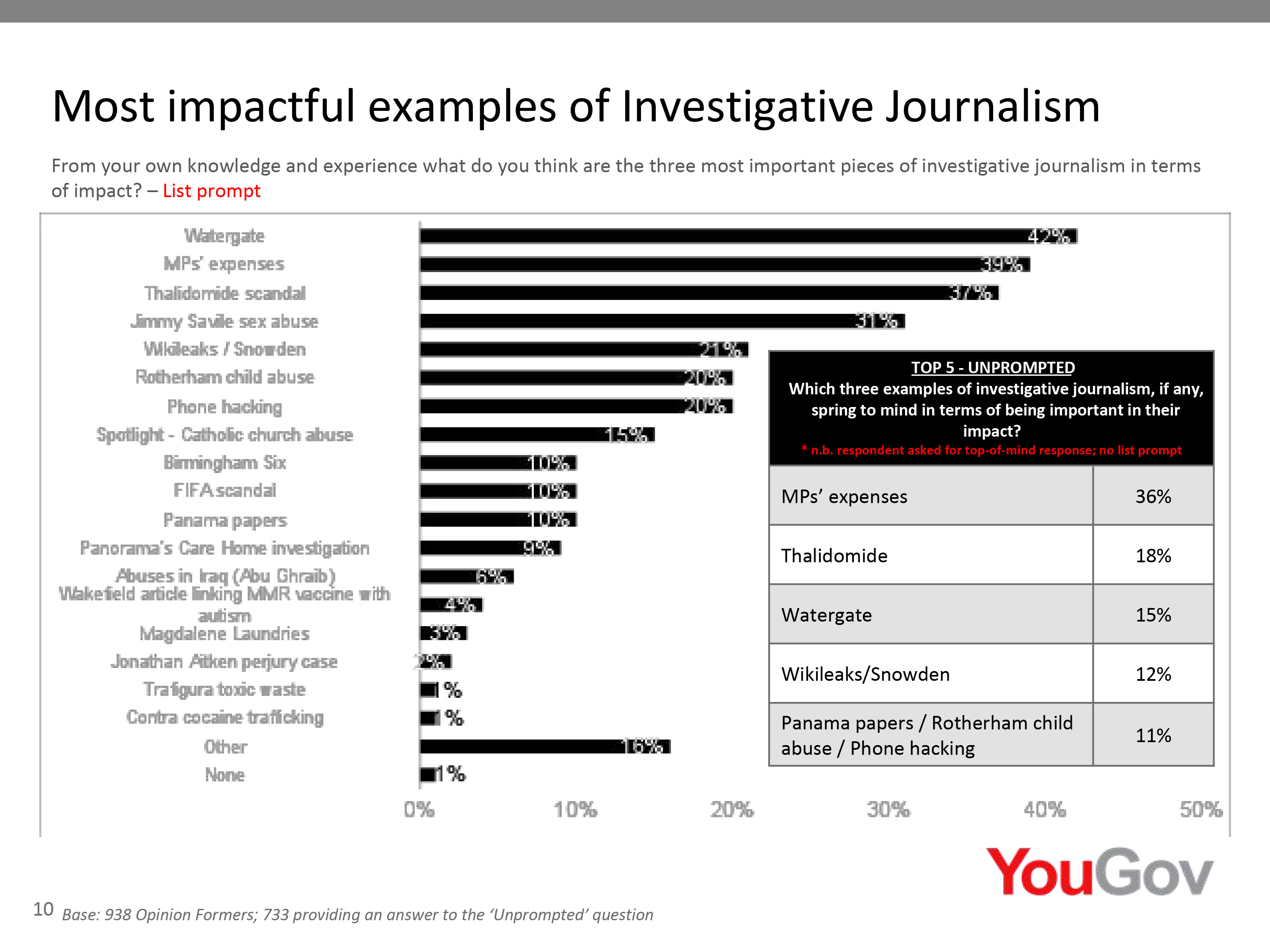

We also commissioned a YouGov survey of a representative sample of opinion formers, both in the UK and in Brussels, to gauge their views of impact in journalism. There was widespread agreement that investigative journalism can have impact on consumer behaviour, on policy-makers and can also set a broader media agenda. Over three-quarters of those polled believed that investigative journalism was an important pillar of the democratic process. Strikingly, when asked which investigations had most impact, many of those surveyed singled out the Watergate Scandal and Thalidomide, as well as other scandals (a good number of which involved vulnerable people and children in particular). Hird, therefore, has looked at both Watergate and Thalidomide in the report, as well as scrutinising the Bureau’s drone project and Channel 4’s campaign to shine a light on the aftermath of the end of the civil war in Sri Lanka (see picture of slide above).

Iconic as Watergate is, especially for journalists, Hird argues that the truths of the investigation have been obscured over time. Whilst the reporting was key to Nixon’s resignation, Hird argues, other parts of civil society and the criminal justice system were essential too. “It was not the journalism alone which had the impact. In order for the investigation to gain traction, the legal and political system needed to engage as well..the Watergate story, in its entirety, is a triumph of the checks and balances in the political system.” Reading Hird’s copy, I was also struck by the similarities with the Trump era today; the chapter gave me hope that journalists, working in collaboration with other actors, can hold power to account.

In Chapter Four, Hird turned his attention to a series of films, commissioned by Channel 4, which shone a light on the aftermath of the civil war in Sri Lanka, which ended in defeat for the so-called Tamil Tigers. Callum Macrae, the producer/director for the films, makes a cogent case for how journalists can and should negotiate with campaigners who are also hoping to bear witness to injustice and, in this case, human rights violations. He attacks the use of the word impartial in this context (something with which I would agree, having filmed with the BBC in Rwanda, after the genocide).

Macrae is quoted in the report as saying: “If you are are impartial between the rich and powerful and the poor and vulnerable, then you preserve the status quo. So I think the word ‘impartial’ is all too often used as a kind of device or fig leaf to cover up what is shoddy, complacent and compliant journalism which does not attempt to speak truth to power.”

In the final chapter, Hird turned his attention to the Bureau’s own drone project, in which we have sought to increase transparency of the covert drone war by the US against targets in four countries – Somalia, Pakistan, Yemen and Afghanistan. Our contention, from the beginning of the project, has been that civilian casualties have been far higher than the US has ever admitted. Just as in Vietnam, they are the collateral damage of a war that may spare the lives of American troops – but not of citizens in those countries, including children. As for impact, Hird notes that it has been significant – the drones programme under President Obama was made more transparent and civilian deaths fell. Other groups have also increased their scrutiny of this hidden war. However, since President Trump took office, deaths have risen sharply and the US led NATO mission in Afghanistan has stopped providing us with strike data. Despite this, our work shows, in Hird’s assessment, “sustained commitment..impact is achieved by the interaction between the journalism and other civil society organisations and the political process.”

Hird concludes that investigative journalism works and can have an impact. Journalists need to be tenacious and bloody-minded if they want to change government policies, bring down the corrupt and save lives. Until now, Hird says, we haven’t had to identify the mechanisms by which journalism achieves its end. But we do now, because, frankly, impact is, as Hird says, “a measure of success and therefore a route to an important source of funding for public interest journalism”.

But funding alone, in my view, probably isn’t what gets most journalists up in the morning. On a personal level, when I look at the journalism I’ve been proudest to be part of, it’s been about results in the real world. From getting war criminals sent to the Arusha war crimes tribunal, to a Guardian front page splash on Turkey Twizzlers, leading to them being taking off school menus, to campaigning for disability hate crime to have parity with other similar crimes, I’ve always been interested in measurable change for the person on the street, whether they are a genocide survivor in south-east Rwanda, a disabled person or even my own school-age daughter and her peers. (And, of course, with these campaigns reform wasn’t achieved by reporting alone.) I suspect I’m not alone in feeling that journalism matters on a visceral level to many reporters.

But impact in journalism is best achieved, as Hird recommends in this valuable report, when lots of other organisations can work with us to achieve an aim on which we can all agree – mediated, to some extent, by the work of an impact producer, as Hird argues.

Lastly, I was struck by Hird’s emphasis on collaboration, whether it was with fellow journalists or with other key figures – law-makers, academics, charities and whistleblowers. The phrase from the disability movement, “nothing about us, without us” is timely right now. As our new network, Bureau Local does already, to some extent, we need to shift position and, where appropriate, align ourselves alongside what Dan Gillmor has termed the “former audience”, who can participate in what we do, rather than see ourselves as set apart from civil society. Then the impact we seek to achieve will be clearer from the outset – and useful to those who entrust us with their stories.